@ahmetgunestekin

@ahmetgunestekin

On the upper battlements of a historic citadel, dozens of brightly painted coffins bearing the initials of fallen Kurdish civilians were put out. Thousands of people were slain or imprisoned during decades of conflict, as evidenced by a wall of street signs containing the names of other victims and a towering mound of rubber shoes.

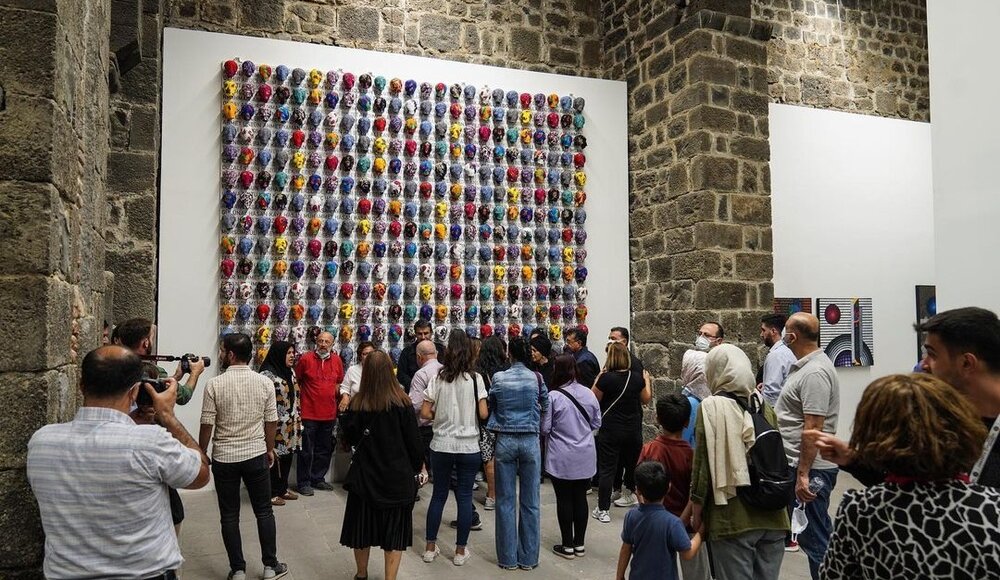

The works were part of a recent art exhibit in Diyarbakir, Turkey's largest Kurdish city, that the organizers thought would help to improve an area that had been ravaged by years of debilitating strife. Instead, the event drew a barrage of criticism from Turks and Kurds alike, prompting the government to cancel it early – a reminder of how divisive the Kurdish issue remains in Turkey. "As a Kurdish artist, I wanted the audience to see and confront the terrible reality," said Ahmet Gunestekin, the artist at the center of the controversy. "I wanted tourists to be confronted with the people of this region's misery."

In 2015, the conflict between Turkish government forces and Kurdish insurgents reached Diyarbakir, destroying the famous old town of Sur with its maze of narrow lanes. Since then, the city has been under strict police control while local Kurdish officials and activists have been imprisoned by Turkish authorities. The city's chamber of commerce had hoped that by luring visitors and filling hotels, the show would provide Diyarbakir a much-needed boost. Mr. Gunestekin was chosen by the organizers because he is well-known internationally and his work celebrates the country's Kurdish minority. In his favor was the fact that he had long been backed by members of Turkey's ruling party.

"Memory Chamber," a show that incorporated political art and video installations, was a combination of painting, textiles, and sculpture that recounted the suffering of Kurds and other minorities over decades of tyranny under Turkish authority. The reaction was more about how politicized Turkey has become under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan than about the quality of the art. Mr. Erdogan secretly advocated increased cultural liberties for Kurds when he first came to power over two decades ago, especially in media and publishing, and in 2013, he supported a peace process with Kurdish separatist fighters. He has presided over the shelling of Kurdish cities and a merciless assault on Kurdish leaders and activists since the peace process collapsed in 2015.

In many ways, the response to the art display, which debuted in October, exceeded expectations: a celebrity-studded opening, massive crowds, and full hotels. However, it drew a barrage of condemnation from all quarters, even from Turkey's interior minister, Suleyman Soylu. The exhibit, he added, conveyed support for terrorists, a phrase the administration is increasingly using to designate political opponents. He further claimed that Mr. Gunestekin had been manipulated. Mr. Soylu said, "This is the first time I've seen terror use art." Former Erdogan ministers and advisers are among Mr. Gunestekin's pals. Because of his cachet, as well as his commercial and financial success, he has been able to venture where other Kurdish artists have not. But that wasn't the first time he'd been chastised, and he seemed to take it in stride. While most of his work reflects his own narrative, he has recently shifted his focus to creating overtly political works.

Mr. Gunestekin was raised by an Armenian stepgrandmother who was an orphan of the genocide in the nearby town of Batman and then in Diyarbakir. He credited his mentor, Turkish literary great Yasar Kemal, for influencing him. He said he was affected by multiethnic craftsmen in his boyhood neighborhood, years of traveling Kurdish villages and listening to stories, and his mentor, the Turkish literary giant Yasar Kemal. Two occurrences dominated his thoughts as he prepared for the recent show, he said. The first was when Turkish military jets struck a group of smugglers crossing the border from Iraq in the town of Roboski in 2011, killing 34 Kurds. In 2015, combat broke out between Kurdish insurgents and Turkish government forces in Diyarbakir's old quarter.

The names of victims who vanished or whose deaths were never investigated are listed on a wall of street signs. Another installation was built using material collected from the wreckage of demolished residences in the historic district, spray-painted gray, and hung on the wall.

The loss of the Kurdish language, which Turkey had forbidden for many years, was investigated through video installations. In one, actors say Kurdish letters that don't exist in the Turkish alphabet. In another, two men use leather straps to pound the letters inscribed in chalk on a blackboard until they vanish. Mr. Gunestekin is not the only contemporary artist to address these issues, but his exhibition in Diyarbakir was by far the largest and most visible in the conflict's history. The art show's central struggle has lasted more than three decades and claimed the lives of an estimated 40,000 people, the majority of whom are Kurds. The separatist Kurdistan Workers' Party, or P.K.K., was opposed to the Turkish government. The pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party, or H.D.P., a legal political party that shares much of the P.K.K.'s political platform, is frequently accused of terrorism for its ties to the militants, and Turkish authorities have imprisoned dozens of its elected representatives, as well as journalists and activists.

The launch of the show revealed a recent political shift in Turkey. A coalition of Turkish opposition groups, founded three years ago to depose Mr. Erdogan, has been working with the H.D.P. to pool their voting power ahead of the 2023 elections. Opposition figures such as Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, a presidential candidate, and Mithat Sancar, a leader of the pro-Kurdish H.D.P., were among the important visitors at the opening. Officials from the government stayed away. Young Kurds expressed their dissatisfaction by flinging one of the metal coffins from the battlements, ostensibly protesting that the show did not go far enough to honor all those who died. But the biggest fury raged on social media, where Mr. Gunestekin interacts with his one million Instagram followers frequently. Guests who danced at reception were also chastised for posing for pictures in front of memorials to pain.

Some see Mr. Gunestekin as a symbol of what they despise about Mr. Erdogan's rule: the prosperity of those with political ties. Most Kurdish artists would have been unable to put up such an exhibition, according to one local artist. Many people have been imprisoned in Turkey for making political remarks. Local Kurdish modern artists' work is far more guarded, an indication of the imposed self-censorship experienced by most artists. Some residents claimed that a "Memory Chamber" was unnecessary because they were still being oppressed by the Turkish government.

"We have lived what he tries to express," said Nusret, a 30-year-old barber who only supplied his first name to avoid government repercussions. "Our anguish hasn't subsided yet. What is the point of exacerbating our suffering?" However, there was no denying the enthusiasm of many of those who visited the show throughout its two-month run, with lines forming on weekends.

Pinar Celik, a 38-year-old Ankara teacher, stated, "I walked around with a lump in my throat." "This is an artist who grew up in our culture and confronted us with concerns that we were attempting to ignore or cover-up." Many claimed they didn't entirely comprehend the piece, but that the Kurdish imagery and customary use of vivid colors were familiar. Yildiz Dag, a Kurdish woman on the battlements, looked out over the colourful coffins and said only one word: "oppression.""Seeing them makes us sad," she said. "However, it is important to demonstrate this so that it does not happen again."

Jean Dubreil

Jean Dubreil