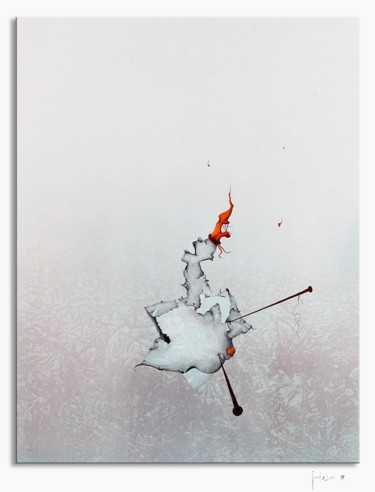

Vava Venezia, Venus in candy land, 2020. Digital art, photomontage on aluminum, 45 x 75 cm.

Vava Venezia, Venus in candy land, 2020. Digital art, photomontage on aluminum, 45 x 75 cm.

Sixteenth-century Florence: Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino

Imagine yourself walking in the Florence (Tuscany) of the 1500s, having the opportunity to take a close look at the recent and laborious building of the Duomo, the adjacent and older baptistery, but also the iconic buildings, also located in the current historic center, of the Church of Santa Maria Novella, the Loggia dei Lanzi, Palazzo Vecchio, etc. Now that you are in the cradle of the Renaissance you can think, that, in the aforementioned places, almost unchanged in the modern age, lived and worked the greatest artists in the history of art, among them, a master and two of his students: Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. I believe there is no better way to present these three great creative geniuses, while also highlighting the differences in their way of working, than to describe some of their best-known masterpieces, which were born and conceived in the above-celebrated region of Tuscany. Speaking of Andre del Sarto, the Florentine artist born in 1486, defined by Giorgio Vasari as a painter "without errors," is officially recognized by critics as the master of the first generation of "eccentrics," that is, of those pupil-pioneers of pictorial Mannerism, such as Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, who aspired to a model of perfect art, capable of surpassing the beauty of nature in a completely nonconformist, "expressionist," blatant and perspective-daring way. Returning to Andrea del Sarto, he, unlike the other two just mentioned, did not use unscrupulousness in his art, in order to "re-propose" a traditional-type repertoire in a graceful manner, within which compositions take shape in which the monumentality of the figures, the variation of colors and technique, and the use of the most modern cues available are accentuated. Such stylistic features are embodied in one of the master's most celebrated masterpieces, such as The Madonna of the Harpies, a 1518 work preserved at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, in which the Virgin standing on a plinth with the Child Jesus in her arms has been depicted in the center of the panel. In this context, the Madonna's legs are supported by two angels with colorful feathers, who, at their sides, accommodate the figures of Saints John the Evangelist and Francis, depicted in a manner akin to their more traditional iconographies. The Madonna of the Harpies, which takes its appellation precisely from the aforementioned mythological figures carved on the base, identified by Giorgio Vasari, could also change its name, since, today's critics, recognize in the aforementioned monsters the most probable depiction of locusts, which, precisely John, immortalized at the side of the Virgin with a book, described in Apocalypse. In fact, in the very ninth chapter of the Book of Revelation, he announces the coming of these monstrous beings, described as figures with women's heads and bellies resembling breastplates of iron, capable of bringing torment to all human beings lacking the seal of God on their foreheads (tau). In this context, the choice to depict St. Francis, angel of the sixth seal, who, in John's prophecy, would carry the tau with him in order to mark the faces of the elect, would also be justifiable.

Andrea del Sarto, Madonna of the Harpies, 1517. Oil on panel, 207 x 178. Florence: Uffizi.

Andrea del Sarto, Madonna of the Harpies, 1517. Oil on panel, 207 x 178. Florence: Uffizi.

Pontormo, Transporting the Dead Christ, 1526-28. Egg tempera on panel, 313 x 192 cm. Florence: Church of Santa Felicita.

Pontormo, Transporting the Dead Christ, 1526-28. Egg tempera on panel, 313 x 192 cm. Florence: Church of Santa Felicita.

Rosso Fiorentino, Deposition of Volterra, 1521. Oil on panel, 375 x 186 cm. Volterra: Pinacoteca and Museo Civico.

Rosso Fiorentino, Deposition of Volterra, 1521. Oil on panel, 375 x 186 cm. Volterra: Pinacoteca and Museo Civico.

Leaving the "apocalyptic" context behind, let us continue our story, in regard to the three Florentine talents, by talking about Pontormo, an artist born in a district of the present-day town of Empoli (Florence) in 1494, a place from which he moved to the Tuscan capital in order to frequent the workshops of Piero di Cosimo, Andrea del Sarto, Mariotto Albertinelli and Fra Bartolomeo, as well as to establish sporadic contacts with Leonardo da Vinci. In this rich creative environment he was recognized, even by great artists such as Raphael and Michelangelo, as a kind of child prodigy of painting, a characteristic that would lead him to venture into experimentation and innovation, which, in his time, was not often understood, so much so that Vasari judged his work to be somewhat bizarre, immoderate and excessive. This viewpoint is now largely superseded by critics, who recognize in the aforementioned master a talented artist capable of devising his own, anti-traditional and anti-classical style of painting, found in works of art such as the Deposition (c. 1526-1528), where his distinctive stylistic features gave a particular interpretation to a subject widely investigated by artists of all times. In fact, however, the more appropriate title for the masterpiece of c. 1526 would be the Transporting of Christ, since, in a somewhat original way, the work depicts no cross, alluding, rather, both to the episode in which Jesus' dead body is carried toward the tomb and the episode in which it is mourned. Similarly, an earlier work by Raphael, namely the Borghese Deposition of 1507, had also combined themes related to the latter two episodes within its composition. Returning to the description of the Tuscan masterpiece, preserved in the Capponi Chapel of the Church of Santa Felicita (Florence), it depicts two young men intent on supporting the body of Jesus, while the Virgin, who is observing the scene, is being rescued by the women present. This composition, also including the figures of Nicodemus and St. John, was conceived as a spectacular representation, rich in emotional reactions, which, translated into refined and elegant visual effects, can be considered a highly visionary stylistic manifesto. A few years earlier, on the other hand, is Rosso Fiorentino's Deposition, an oil on panel painting from 1521 preserved at the Pinacoteca di Volterra (Tuscany), a painting within which Christ is deposed from a cross with a massive structure, capable of creating, together with the wooden staircase a powerful scenic machine, within which are included, both the characters intent on laying the lifeless body, among whom Nicodemus and Joseph Arimathea are recognizable, and the Virgin supported by two women, the kneeling Magdalene, the boy holding the ladder, and the apostle John in tears. The innovative aspect of the work lies in multiple factors; first, Rosso painted a moment in Christ's story hitherto underrepresented, namely the precise moment when, immediately after the detachment of his body from the cross, he was descended through the uncertain support of the men's hands and arms, an unstable detail intended to generate a strong tension and suspension in the painting. Secondly, the scene, set at the twilight described in Matthew's account (27:45; 57), is marked by a literal emotional explosion, conferred by the contrast between the static arrangement of the cross and the ladder and the dynamism of the men on the cross, which is repeated, further down, in the less problematic movement of the Magdalene. Finally, making a quick comparison between Pontormo and Rosso, the feature that makes the former's work dramatic is the lack of perspective space, a peculiarity intended to give the characters a great sense of instability, which turns into insecurity and anguish, while the dismay of the second masterpiece is mainly due to the angular volumetry of the "deformed" bodies in movement, as well as the predominance of red hues. Finally, in this context, it is good to point out that this tale represents only a small part of the immense history of Tuscan art, a region that has been the home of great masters, such as Giotto, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Cimabue, Piero della Francesca, Amedeo Modigliani, etc., as well as the cradle of contemporary talents, such as, for example, Karim Carella, Francioni Mastromarino and Simone Parri, original and innovative artists of Artmajeur.

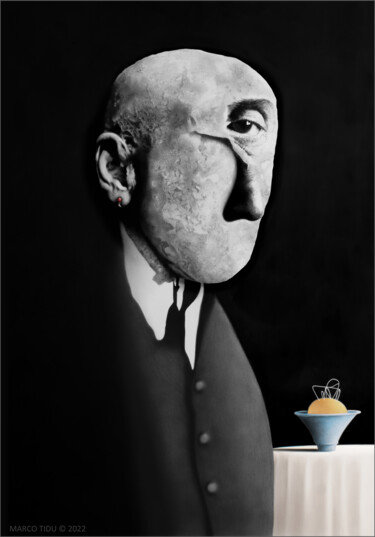

Andrea Pisano, Cardinal #01, 2020. Digital art, digital painting / photomontage / 2D digital work on paper, 100 x 70 cm.

Andrea Pisano, Cardinal #01, 2020. Digital art, digital painting / photomontage / 2D digital work on paper, 100 x 70 cm.

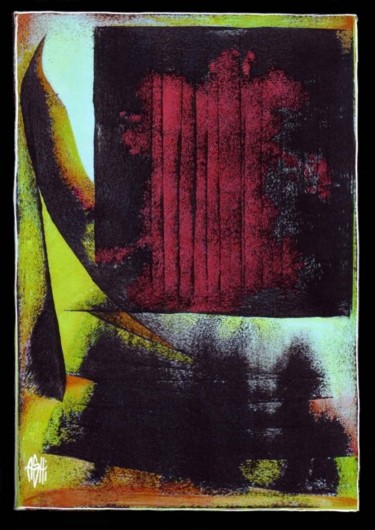

Paolo Rizzi, Deviless I, 2021. Oil on cardboard, 106 x 65 cm.

Paolo Rizzi, Deviless I, 2021. Oil on cardboard, 106 x 65 cm.

Karim Carella, Cypress trees at sunrise, 2017. Digital photograph on paper, 80 x 80 cm.

Karim Carella, Cypress trees at sunrise, 2017. Digital photograph on paper, 80 x 80 cm.

Karim Carella: Cypress trees at sunrise

If the Tuscan landscape, home of artists and poets par excellence, could self-describe itself with one word, he would surely choose CIPRESSI! In fact, most of the postcards of Tuscany, which are in circulation to this day, have immortalized the landscapes of the Val d'Orcia, marked by the presence of the aforementioned tree, which, arranged in rows on ridges, has those typical columnar features with narrow bearing, also characteristic of Carella's photograph. Nevertheless, it is good to make it known that the cypress is actually native to the eastern Mediterranean basin, an area from which it was imported to Italy by the Phoenicians, Greeks and Etruscans. In fact, its ancient presence in the Tuscan land can also be found within classic masterpieces of art history, among which the works of Beato Angelico, Paolo Uccello and Leonardo da Vinci certainly stand out. Speaking of the latter great master, it is impossible not to refer to the Annunciation of 1472, a panel painting preserved in the Uffizi Gallery in which, in front of a Renaissance palace, equipped with a lush garden, the Archangel Gabriel kneels before the Virgin, greeting her while handing her a lily, a symbol of purity. Just such a vision, set in the aforementioned naturalistic location, is surrounded by the presence of the profile of four tall cypress trees, which, in the twilight light, alternate with other rich and flourishing plants. As a result, the photograph by the Tuscan Carella acquires additional meanings, aimed at placing it within a great history and artistic tradition in constant evolution.

Francioni Mastromarino, Leonardo da Vinci, 2021. Terracotta sculpture and other substrate, 40 x 35 x 32 cm / 15.00 kg.

Francioni Mastromarino, Leonardo da Vinci, 2021. Terracotta sculpture and other substrate, 40 x 35 x 32 cm / 15.00 kg.

Francioni Mastromarino: Leonardo da Vinci

We could simply limit ourselves to interpreting the Leonardo da Vinci sculpture with a phrase/slogan: a Tuscan, paying homage to and interpreting another Tuscan! In fact, Florentine Eleonora Francioni, who together with Antonio Mastromarino constitutes the artistic duo Francioni Mastromarino, currently active in Pietrasanta (Tuscany), has created, through the aforementioned association, a work having probably the intent to celebrate Leonardo da Vinci, undisputed genius of the art world of all times, born in Vinci (Tuscany) in 1452. In particular, Francioni Mastromarino's sculpture would seem to be inspired precisely by the Self-Portrait, which the Tuscan artist executed in 1517, now preserved in the Royal Library of Turin. This sanguine drawing on paper depicts the master in the last years of his life, a period when, by then elderly, with a long and thick beard and a frowning look, he was spending the twilight of his existence in France, the country where he had been called to the service of Francis I. It is precisely the aforementioned depiction that is considered to be not only an icon in the history of art, but also the only true portrait of the artist to which we still refer today when we try to imagine the features of the Italian genius. Nevertheless, many scholars think, that Leonardo is not the man in the sanguine, as, at the time the drawing was made, long beards and hair were not fashionable. In addition, the master at the age of 63, the period to which the work dates, was stricken with an illness that had reduced his ability to articulate his right hand, a fact that would not have allowed him to make the details present in the self-portrait. Despite these doubts about the dating and identity of the effigy, one certainty remains: the immortality of Leonardo's work lives on in the work of the Artmajeur duo.

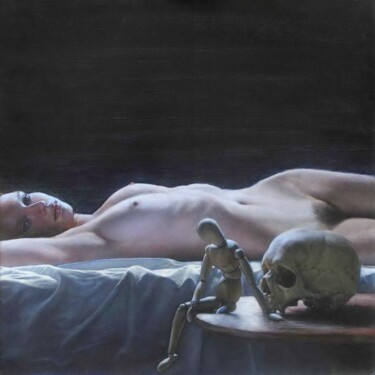

Simone Parri, Why different?, 2016. Wood and plastic sculpture, 107 x 76 x 5 cm / 2.00 kg.

Simone Parri, Why different?, 2016. Wood and plastic sculpture, 107 x 76 x 5 cm / 2.00 kg.

Simone Parri: Why Different?

Through Simone Parri's work we return once again to Florence, a city in which the artist works inspired, however, by a context that is, at times, decidedly more international, so much so that his Why Different?, arguably aimed at promoting the acceptance of differences, perhaps echoes the work of Július Koller (1939-2007), one of the most important Eastern European artists active since the 1960s. In particular, the Artmajeur artist's sculpture can be compared to Question Mark b., a 1969 work made through the use of a wooden tray with two ornate handles, which Koller covered with white paint and, subsequently, engraved with a large question mark. Such an object, described by the Slovak himself as "anti-painting" , represents a symbol of the uncertainty of the socio-political context of Czechoslovakia at the time, the country where Koller lived and worked. In fact, in the latter place, after 1968, the political situation became more repressive, such that avant-garde artistic production became mainly a private activity. Nevertheless, Koller rejected the more traditional academic art, choosing to follow the more "subversive" movements, such as Dada, Nouveau Réalisme, the Situationist International and Fluxus. Finally, it is good to make it known how, even with regard to the works of the conceptual group "U.F.O," such artist used the question mark, in order to escape the harsh political situation, finding refuge in parallel realities, such as extraterrestrial life forms.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli